Frank Woodhull’s Ellis Island Experience

In October 1908, 50-year-old Canadian-born immigrant Frank Woodhull joined the line of steerage passengers awaiting inspection at the Ellis Island Immigration Station. Woodhull, who had resided in the U.S. for several years but never became a citizen, had just returned from an extended tour through Europe. As the line of immigrants filed past Ellis Island doctors, Woodhull was pulled aside for further screening. The doctors noted his “slight” build and “sunken cheeks” and suspected he might be afflicted with tuberculosis, a contagious disease that would render him inadmissible.

Woodhull was moved to an examination room and asked to remove his clothes. After first refusing, Woodhull explained the he was biologically a woman. The doctors brought in a female matron who confirmed the claim and completed the examination, finding nothing physically wrong with Woodhull. Immigration Service Officials determined that in addition to sound health, Woodhull had enough money to avoid being considered “likely to become a public charge,” and behaved rationally and respectably. Nevertheless, they decided to investigate the case further.

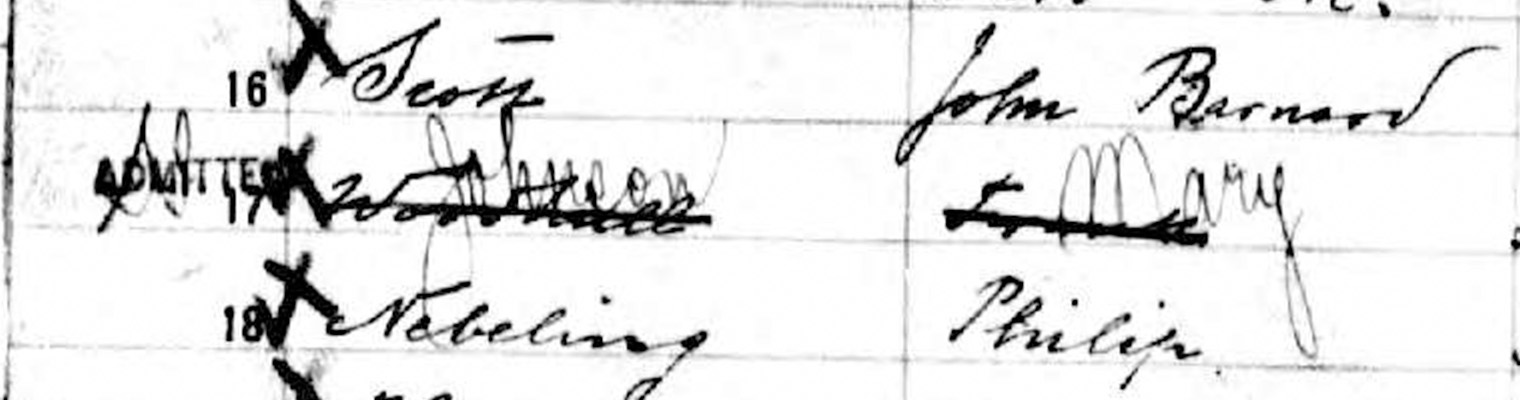

Image: Ellis Island employee Augustus Sherman’s portrait of Frank Woodhull.

At a hearing in front of the Board of Special Inquiry, a panel of immigrant inspectors who determined the admissibility of immigrants held for further questioning, Woodhull related his life story. Born as Mary Johnson, he explained that his appearance, which included a slight mustache, had made his early life difficult. Finding work had been especially hard. So, at age 35 he bought men’s clothing and began living as a man. As Frank Woodhull, he found profitable work as a bookseller and lived a “life of independence and freedom.” Woodhull’s testimony impressed immigration officials. They wondered, though, if his manner of dress could run afoul of state laws.

The Immigration Service held Woodhull overnight while determining his fate. Since he refused to wear women’s clothing and immigration officials would not place him in the men’s detention rooms, he slept in a private room in the hospital. At some point during his stay he sat for a portrait taken by Ellis Island clerk and avid photographer Augustus Sherman.

Ultimately, immigration officials determined that no federal or state laws prohibited Woodhull from dressing as a man and that he could not be denied admission to the country based on his appearance. As one newspaper put it, he was “deemed a desirable immigrant who should be allowed to earn [his] livelihood as [he] saw fit.”

Woodhull’s story was reported in the New York Times and in newspapers across the country, which caused a momentary stir. The reporting made it clear that he did not seek out the attention. In fact, little is known of what became of him after he left Ellis Island. It’s presumed that he traveled to New Orleans, where he intended to settle, open a business, and return to a life of welcome anonymity.

Because Woodhull’s arrival at Ellis Island occurred more than a century ago, it is difficult to know how he would have identified himself. His testimony emphasized the utility of men’s clothing and he indicated that he began dressing a man to earn a better living. Many aspects of his behavior, including his absolute refusal to put on women’s clothing even when threatened with exclusion from the U.S., suggested a deeper identification as a man. In any case, it is clear that Woodhull refused to conform to the gender norms of his time.

While modern terms like “transgender” did not exist 100 years ago, stories like Woodhull’s demonstrate that the concept existed as lived experience. Uncovering these stories provides us with a broader, more-accurate understanding of our past and reminds us that, though not always visible, transgender individuals have long been a part of our nation’s history.

Note: Since Frank Woodhull identified as a male when not forced to do otherwise, this article uses masculine pronouns when referring to him.